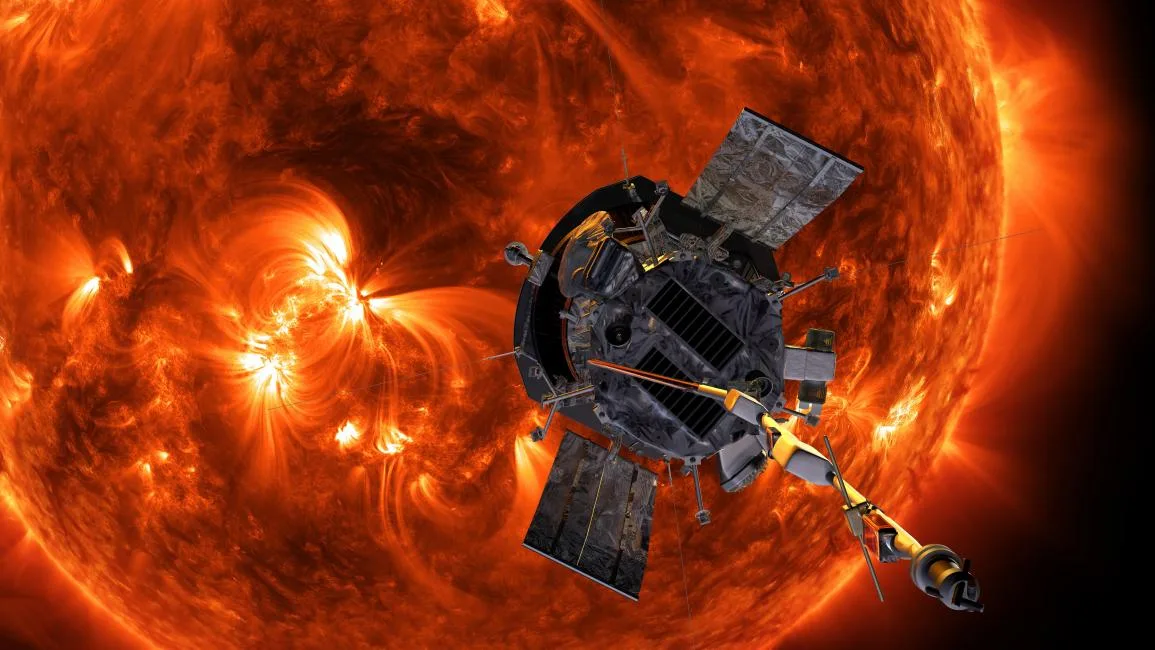

Parker Probe captures stunning new images of the Sun’s secrets

layered coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and detailed flows of the solar wind. These are the closest-ever photos of the Sun, offering scientists unprecedented insights into solar dynamics.

The images were taken during the probe’s closest approach on December 24, 2024, and scientists hope they will deepen understanding of space weather, which can impact everything from satellite operations to power grids on Earth.

“We’ve been waiting for this moment since the late 1950s,” said Nour Raouafi, Parker Project Scientist, to AFP.

Beyond what we’ve seen before

The Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018, is named in honor of astrophysicist Eugene Parker, who first described the solar wind in 1958. During recent orbits, the probe reached as close as about 601,000 km from the Sun’s surface—a record first set on Christmas Eve 2024 and repeated since then.

If the distance between Earth and the Sun were scaled to just 1 km, Parker would now be only about 40 meters away.

Capturing the invisible

The probe’s only camera, WISPR (Wide-field Imager for Parker Solar Probe), captured high-resolution footage of CMEs—huge blasts of charged particles. These bursts play a key role in space weather, and their effects can be seen on Earth as dazzling auroras.

“We saw many CMEs stacked on top of each other, making them unique. It’s truly amazing to see this dynamic as it unfolds,” said Raouafi.

The images also show solar wind streaming from the left, shaped by a structure called the heliospheric current sheet. This invisible boundary marks where the Sun’s magnetic field changes direction from north to south. Studying it is crucial because it affects how solar eruptions spread and their potential impact on Earth.

Why space weather matters

Space weather can have serious consequences, including overloading power grids, disrupting communications, and damaging satellites. With thousands of new satellites expected to enter orbit in the coming years, managing them becomes increasingly complex—especially during solar storms that can nudge satellites slightly off course.

A mission built to last

The Sun is now heading toward its next solar minimum, expected in about five to six years. Some of the most intense solar storms in recent history, like the famous “Halloween storms” of 2003, happened during such declining phases. During those storms, astronauts on the ISS had to take extra precautions against radiation.

“Capturing one of these massive flares would be a dream come true,” said Raouafi.

The Parker Solar Probe still has far more fuel than initially predicted. This means it could keep flying for decades—until its solar panels degrade and can no longer power the spacecraft. When its mission finally ends, Parker will gradually break apart and, as Raouafi described, “become part of the solar wind itself.”